Winter Term Update: Guillemin Lab Rotation

The Guillemin Lab

The Guillemin lab, as described on the lab website, are…

“In the Guillemin lab, we strive to understand how hosts and their associated microbial communities shape each other. We use genetically tractable and microbiologically manipulable models systems including zebrafish and fruit flies. We explore the reciprocal impacts of microbial communities on their hosts and host environments on resident microbiota during development and in the context of disease. We perform experiments using gnotobiotic animals with defined microbial associations to uncover the causal relationships in these reciprocal interactions and to understand their mechanisms. We investigate host-microbe systems with scalable complexity, from germ-free and mono-associated animals to conventionally reared animals with their full complement of microbes. From these investigations we hope to understand the principles by which complex host-microbe systems functions and to learn how they can be manipulated to promote the health of systems like ourselves.”

I wanted to rotate with Karen and the Guillemin lab because I am extremely interested in the vast interplay that exists between the microbes that we harbor and the potential that they could be impacting us in ways that we rarely think about. I also was very much pulled by the potential of finding mechanistic insights from the work in the Guillemin lab.

Pancreas? Pancreai? Pancreases?

If you look at this picture below, you see an illustration representing the microbial abundance found in everyone. In order to survive, these microbes have to compete with one another and to do this they will often secrete factors that will in one way or another interact with and impact common features of cellular membranes of both other microbes and the host alike.

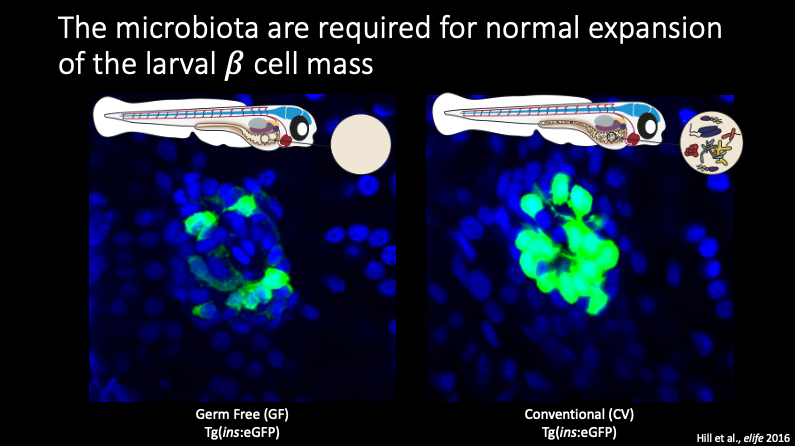

One such example of how the secreted factors from the microbiome can impact development is seen in beta cells within the pancreas. Beta cells are the only cells in the body that can produce and release insulin, so misregulation of the release of insulin and insulin signaling can lead to major bodily disfunction. GF fish, or fish without a microbiome, show significantly decreased beta cell development compared to fish which do have a microbiome.

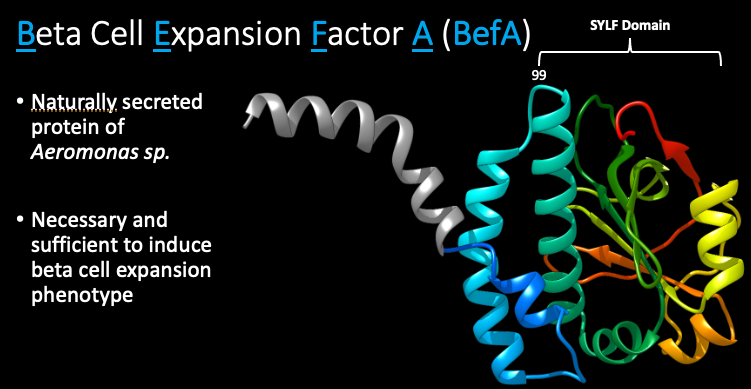

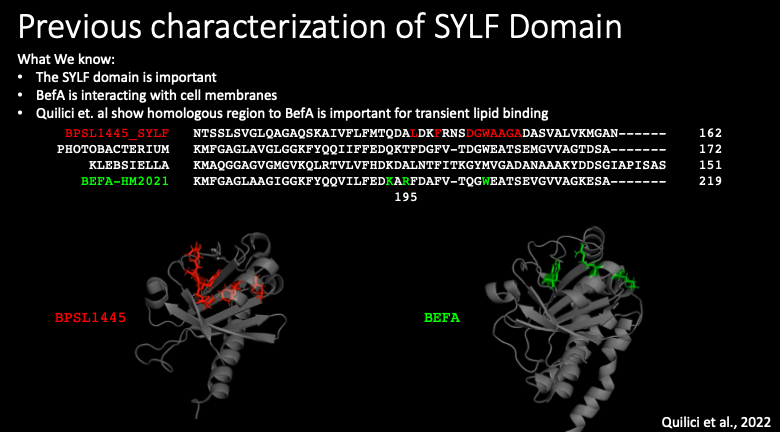

Through a combination of GF zebrafish monoassociations and mass spec analysis, the lab identified a novel protein from Aeromonas veronii that is both necessary and sufficient to induce beta cell expansion in developing zebrafish. The lab named this protein beta cell expansion factor A or BefA. When Emily Sweeney in the lab determined the structure of the novel BefA protein, she found that it contained an SYLF domain. The SYLF domain is a ubiquitous protein domain that is found in many organisms but is rare in prokaryotes. While the exact function and mechanism of the SYLF domain is not known, previous studies have shown that the SYLF domain is important for lipid interactions and is often found in proteins that colocalize with membranes.

Previously, Michelle Massaquoi and Emily in the the lab had used fixed and stained Bacillus and explanted beta cells to show that BefA can localize with membranes of both bacterial and eukaryotic cells after 2 hours. However, because this imaging was done using fixed and stained cells, we were still missing important information of the dynamics of BefA with live cells. And so, while Michelle and Emily had shown that BefA can localize with membranes, this ultimately led to the first major question of my rotation. I first wanted to explore the dynamics underlying BefA’s interaction with cellular membranes.

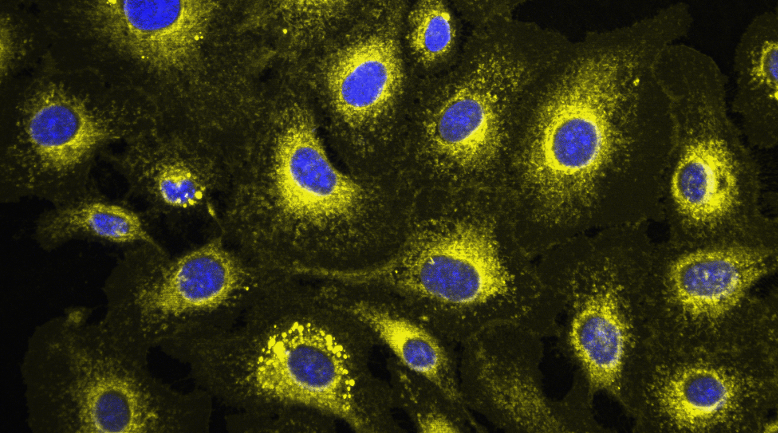

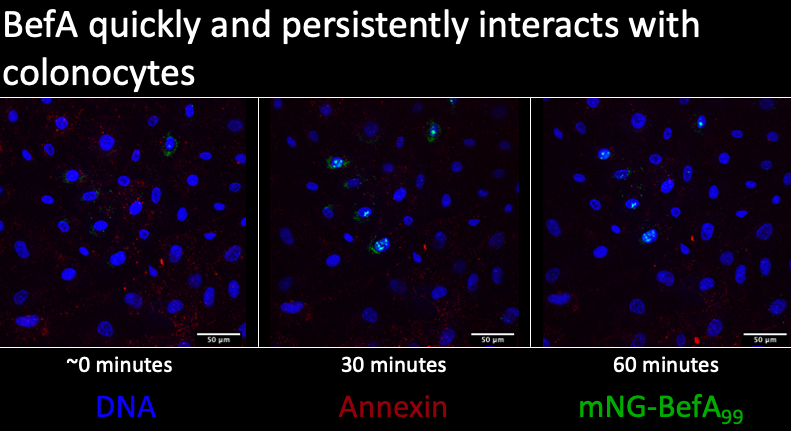

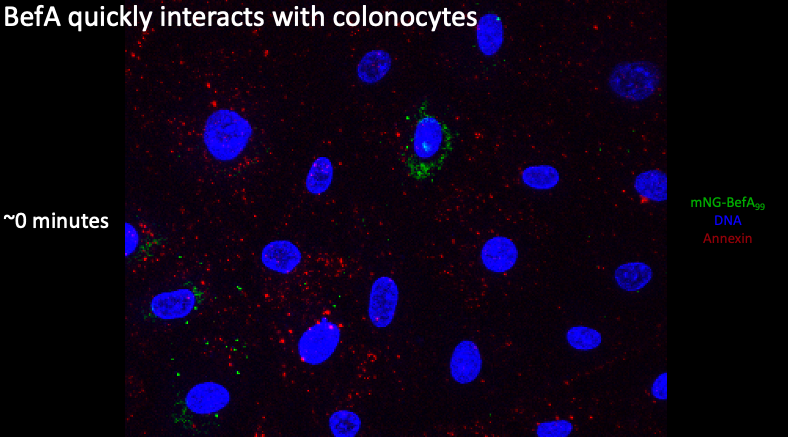

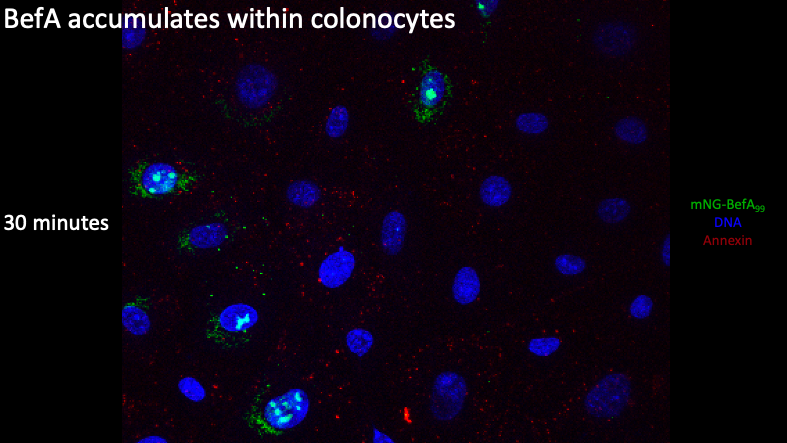

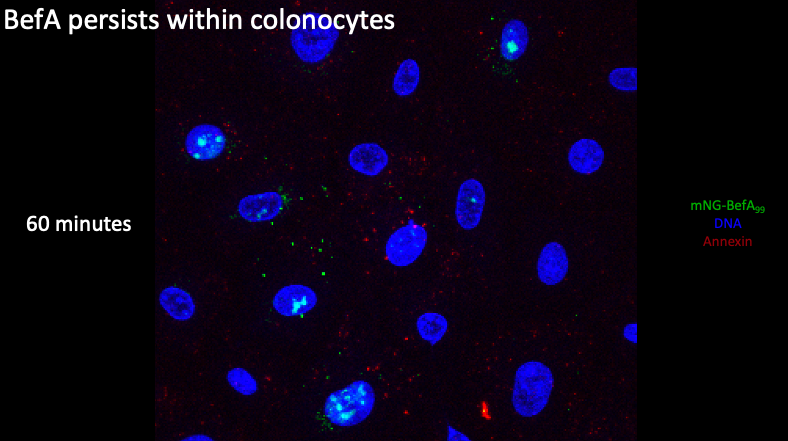

Building upon Michelle’s work, I developed a live imaging protocol using colonocytes and created a time series of BefA’s interactions over time with the colonocytes. The blue is showing DNA within the nucleus and the green is BefA conjugated to the fluorescent mNG protein. The red is labeling phosphatidyl serines in the plasma membrane but this didn’t work as I had hoped so you should ignore this in the images. I saw that BefA forms clusters at the membranes and that this interaction between BefA and cells begins to occur very quickly, within the first five minutes after the BefA was added to the cells.

If we zoom in at our first time point, I saw large clusters of BefA that were able to colocalize with the cells and appear to be within the nucleus, suggesting that BefA can not only interact with and pass through the outer plasma membrane but also potentially interact with the nuclear membrane if it can enter into the cell.

Here at the 30 minute time point, you can see that there is now a significant amount of BefA both inside and outside the colonocyte nucleus, showing that BefA is actively moving into the nucleus as we move through time.

Lastly, if we zoom in at the 1 hour timepoint, we see that BefA is still largely localized within the nucleus but we have lost the majority of the BefA in the perinuclear space. Taken together, all these results recapitulate Michelle’s findings and demonstrate this interaction between BefA and cells occurs quickly and persists through time.

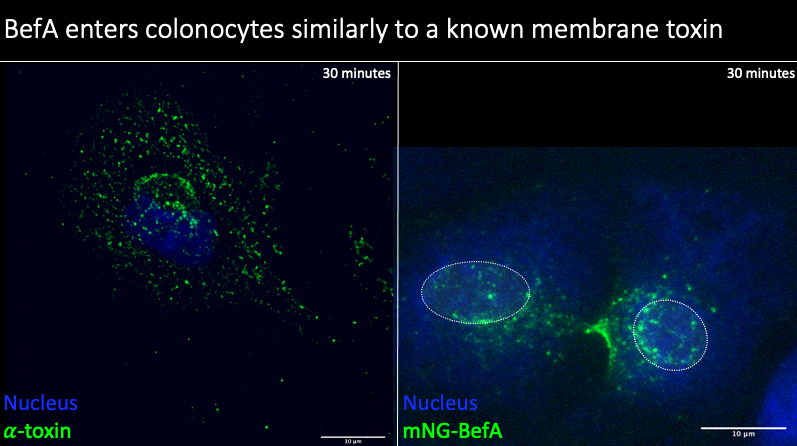

Now that we had seen that BefA could interact with and enter into these cells, I wanted to explore how it compares to another known membrane perturbing protein, alpha-hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus.

Alpha-hemolysin (alpha toxin) is a pore-forming toxin that can lead to cell death with prolonged exposure. On the left here, you can see fixed and stained cells with the nucleus in blue and alpha toxin in green. You can see that the toxin readily enters into these cells, with significant presence throughout the cell. On the right, you are looking at cells treated with BefA, with the nucleus outlined due to some poor staining. In comparison with alpha toxin, I observed more sparse positioning throughout the cell in BefA treated cells. Nonetheless, BefA is still able to enter into these cells, but it’s less widespread nature and large clustering at single points suggest its mechanism of action is likely different than that of alpha toxin.

Additionally, alpha toxin is known to be trafficked to the lysosome of cells in the standard endocytic trafficking pathway. However, like I had previously mentioned based on my live cell imaging, it appeared that BefA was localizing within and around the nucleus of the colonocytes. To try to explore this in more depth, I fixed and stained cells that were treated with BefA to try to get high resolution images of colonocytes to better determine BefA localization. With the help of Adam Fries in the UO imaging core, I created this movie that you are seeing and this does in fact confirm the presence of BefA within the nucleus in my imaging experiments, suggesting that BefA is behaving differently than alpha toxin and forming both perinuclear and nuclear interactions.

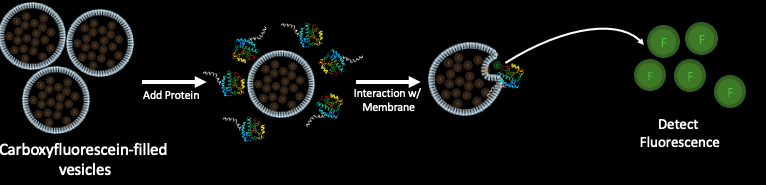

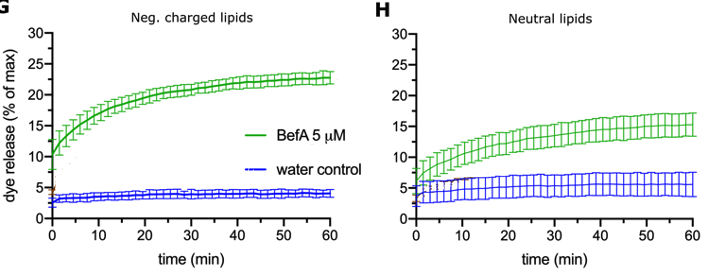

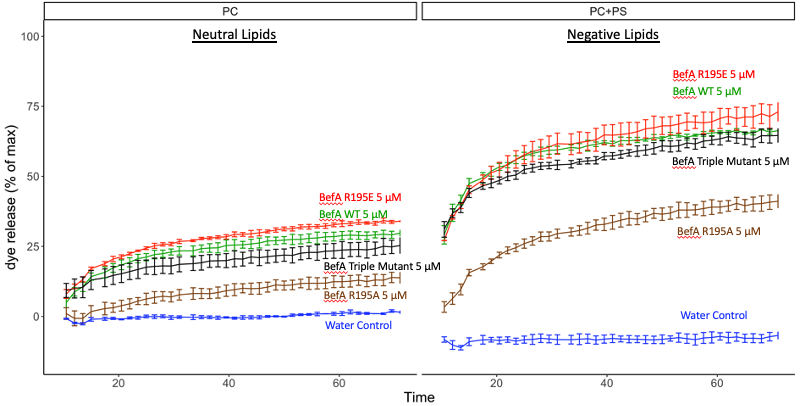

So now that I saw that BefA is interacting with cellular membranes in some way, I wanted to begin to explore some potential mechanisms of BefA’s activity. I discovered that BefA is trafficked in the cell in an unconventional way and I wanted to know if this trafficking is related to its biochemical interactions with membranes. To explore this, I needed to first better understand which parts of the protein determine BefA’s interactions with membranes. In order to characterize BefA’s interactions with membranes, we used a dye release assay that Emily in the lab developed. First, vesicles were filled with carboxyfluorescein dye. BefA was then added to these vesicles and the fluorescence was monitored over time. Since the carboxyfluorescein is packed tightly inside the vesicles and quenched until it is diluted, you can’t detect the fluorescence unless the membrane is perturbed and the carboxyfluorescein is released and diluted. So, in theory, the more membrane perturbation that occurs, the more fluorescent signal should be detected. Below you can see typical results of BefA interacting with vesicles made up of negatively charged and neutral vesicles.

A paper that came out early this year from Quilici and others used NMR to determine a related SYLF domain structure and probed the potential mechanism of this SYLF domain. They found that certain residues (which are shown in red) were important for interactions with lipids. These important residues were found to be very close to BefA residue 195 that Emily previously shown decreased BefA’s activity. If you look at the structures of their SYLF domain on the left and BefA on the right, you can also see that the residues they found to be important (in red) are in a very similar position to the residues we ultimately decided to investigate further that are shown in green. The agreement between our own results and this paper from Quilichi and others suggested that we were looking at the right area underlying BefA’s function.

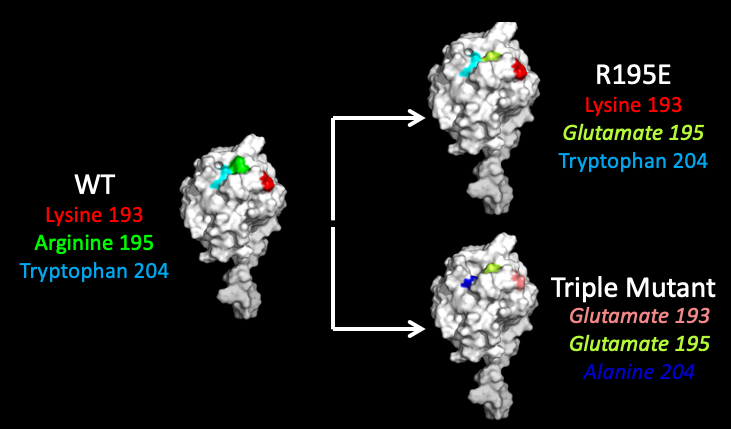

We identified three residues that were in the region identified by Quilici that also appeared to be on the surface of BefA, making them potential locations of interactions with lipid membranes. Like I mentioned before, Emily in the lab had shown a reduction in membrane-perturbing activity when residue 195 in BefA was mutated from the positively charged arginine to the neutral alanine, I first decided to go even further and create a mutant protein with that arginine changed to a negatively charged glutamate. I also made a mutant with two other mutations in the region that Quilici found was important to try to completely break the function of BefA.

Just as a reminder, an increase in fluorescence equals more membrane perturbation. I reconfirmed Emily’s previous result that the R195A mutant did show reduced activity compared to WT. Surprisingly, I found across multiple trials that switching the charge of that 195th residue from positive to negative in the new R195E mutant, which is shown in red here, actually increased the activity of BefA. I did find however that the triple mutant, which is shown in black, demonstrated reduced activity even though it included the bolstering R195E mutation, suggesting that mutations at the other two residues are potentially detrimental for the activity of BefA. However, none of these mutants as poor of activity as the R195A mutant that Emily had tested previously, of course with the caveat that the R195E mutation could be potentially rescuing the function of our mutants.

So overall, at this point I know that BefA quickly internalize within cells. I also repeatedly observed BefA forming cluster inside and outside of cell, and saw that BefA localization within the cells seems to be distinctly different than the well-characterized alpha toxin localization through the endocytic trafficking pathway. My results from the dye release assay with mutant versions of BefA suggest that residue 195 is important for BefAs activity and that the SYLF domain does potentially play a role in BefA’s activity since I was able to alter the activity of BefA by altering this region.

In the future, the lab is hoping to generate new mutants that can then be initially characterized through dye release assays and more live colonocyte imaging. If these experiments show promising results, we expect that this could translate to differences in BefAs activity in ex-vivo and in-vivo experiments. The hope is to observe the interactions that BefA and other mutants undergo with the full pancreas and specifically cells of the islet of the pancreas.

I would like to thank everyone in the Guillemin lab for a really nice and engaging rotation and for creating such a welcoming and supportive environment. I want to thank Karen for the opportunity to rotate in the lab, and I especially want to thank Jen, Emily, and Michelle for all of their hands on help throughout the term. I’d also like to thank Adam in the imaging core, the media kitchen, and Amy from the Stankunas lab for help with imaging.