Spring Term Update: Spero Lab Rotation

The Spero Lab

Hi again everyone! This term I rotated in the Spero Lab. Today I’m going to walk you through the last term and work I did exploring an enhanced growth phenotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

I was really excited to rotate in the Spero lab because even though I have been working with bacteria for years, I had never worked in what you would call a “traditional” microbiology lab! The lab work that I have done before was largely focused on broad systems using sequencing based technologies that make it hard to find distinct mechanisms and dive into the genetic details of bacteria beyond correlations. That is not the case at all in the Spero lab! The Spero lab works with a variety of different mutant lines of bacteria that allow thm to interrogate these genes’ role in the survival and adaptation of the bacteria in the challenging environments that thye may face. Super exciting!

The Spero lab is run my Dr. Melanie Spero, who you might remember from my post about my fall term rotation! Dr. Melanie Spero just opened her new lab at the University of Oregon this year and is interested in studying how bacterial pathogens adapt thier physiology to survive in host environments and how those adaptations affect human health outcomes.  More specifically, they study bacterial physiology in the context of long-term infections, such as the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients and chronic wounds. While the lab is interested in a broad range of topics related to these long-term infections, today I’m going to focus on how these pathogens can evolve over time and how better understanding the impact of these mutations can potentially lead to better efforts to combat these infections. One of the microbes that is found in the majority of these chronic infection contexts is Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

More specifically, they study bacterial physiology in the context of long-term infections, such as the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients and chronic wounds. While the lab is interested in a broad range of topics related to these long-term infections, today I’m going to focus on how these pathogens can evolve over time and how better understanding the impact of these mutations can potentially lead to better efforts to combat these infections. One of the microbes that is found in the majority of these chronic infection contexts is Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

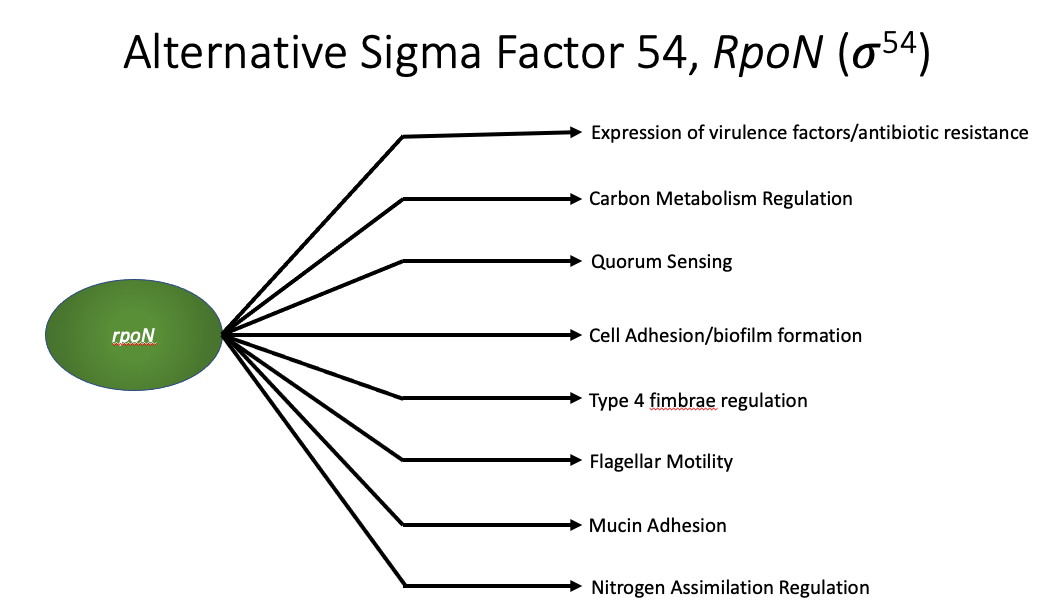

More specifically, I focused on the alternative sigma factor 54 in P. aeruginosa, which I will refer to as RPON from here on out. RPON recruitment during transcription is required for many activities in P. aeruginosa.  Most importantly for what I’m going to talk about today is its connection to carbon metabolism regulation. It has been shown that P. aeruginosa without a functioning RPON are significantly more susceptible to antibiotic treatments. And so in the Spero lab, by studying P. aeruginosa without a functioning RPON, we can start to gain insights into how P. aeruginosa may evolve to overcome a deficient RPON in the context of chronic infections. rpoN mutants are also frequently isolated from chronic lung and wound infections and there seems to be some selective pressure for P. aeruginosa to mutate this gene, so the lab is interested in the physiology of this mutant.

Most importantly for what I’m going to talk about today is its connection to carbon metabolism regulation. It has been shown that P. aeruginosa without a functioning RPON are significantly more susceptible to antibiotic treatments. And so in the Spero lab, by studying P. aeruginosa without a functioning RPON, we can start to gain insights into how P. aeruginosa may evolve to overcome a deficient RPON in the context of chronic infections. rpoN mutants are also frequently isolated from chronic lung and wound infections and there seems to be some selective pressure for P. aeruginosa to mutate this gene, so the lab is interested in the physiology of this mutant.

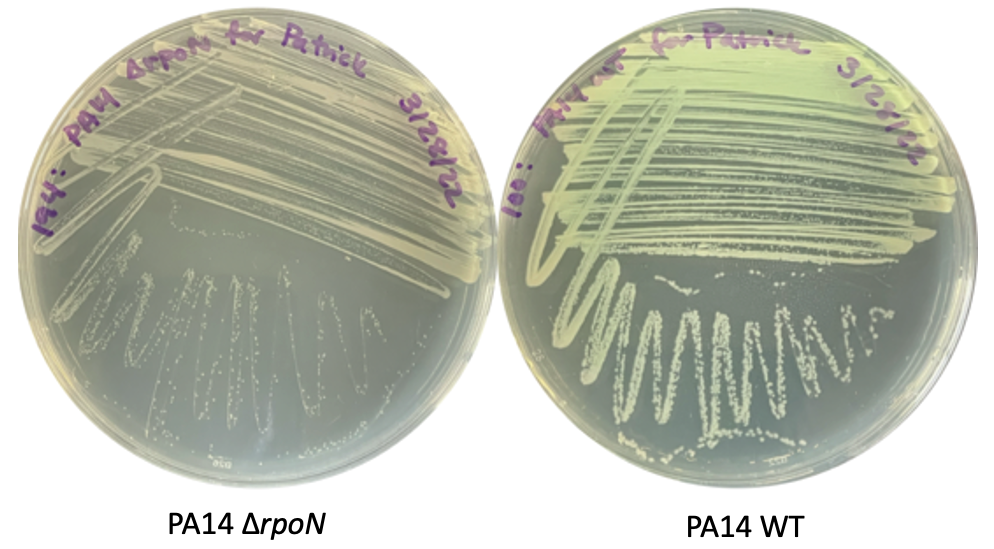

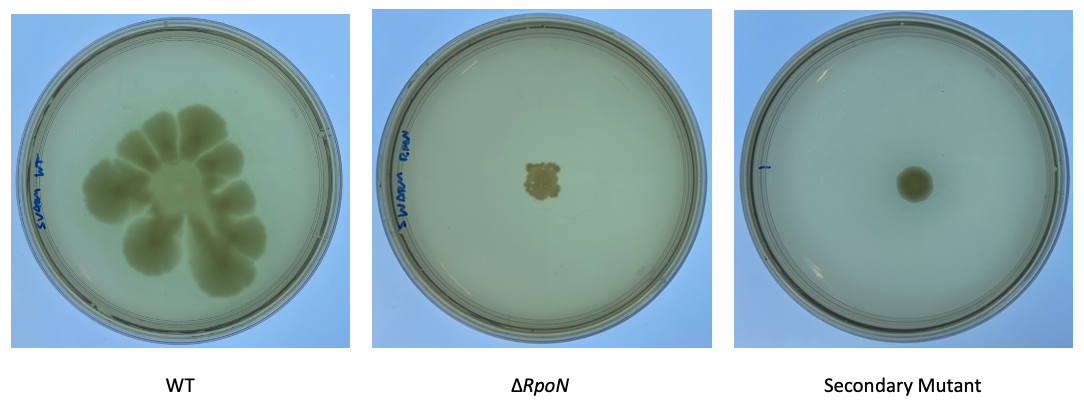

Here, you are seeing some streaks of WT P. aeruginosa on the right and an rpoN knockout strain on the left. I hope you can appreciate that the rpoN knockout strain has significantly smaller colonies and we know that this is from a drastically reduced growth rate over time.

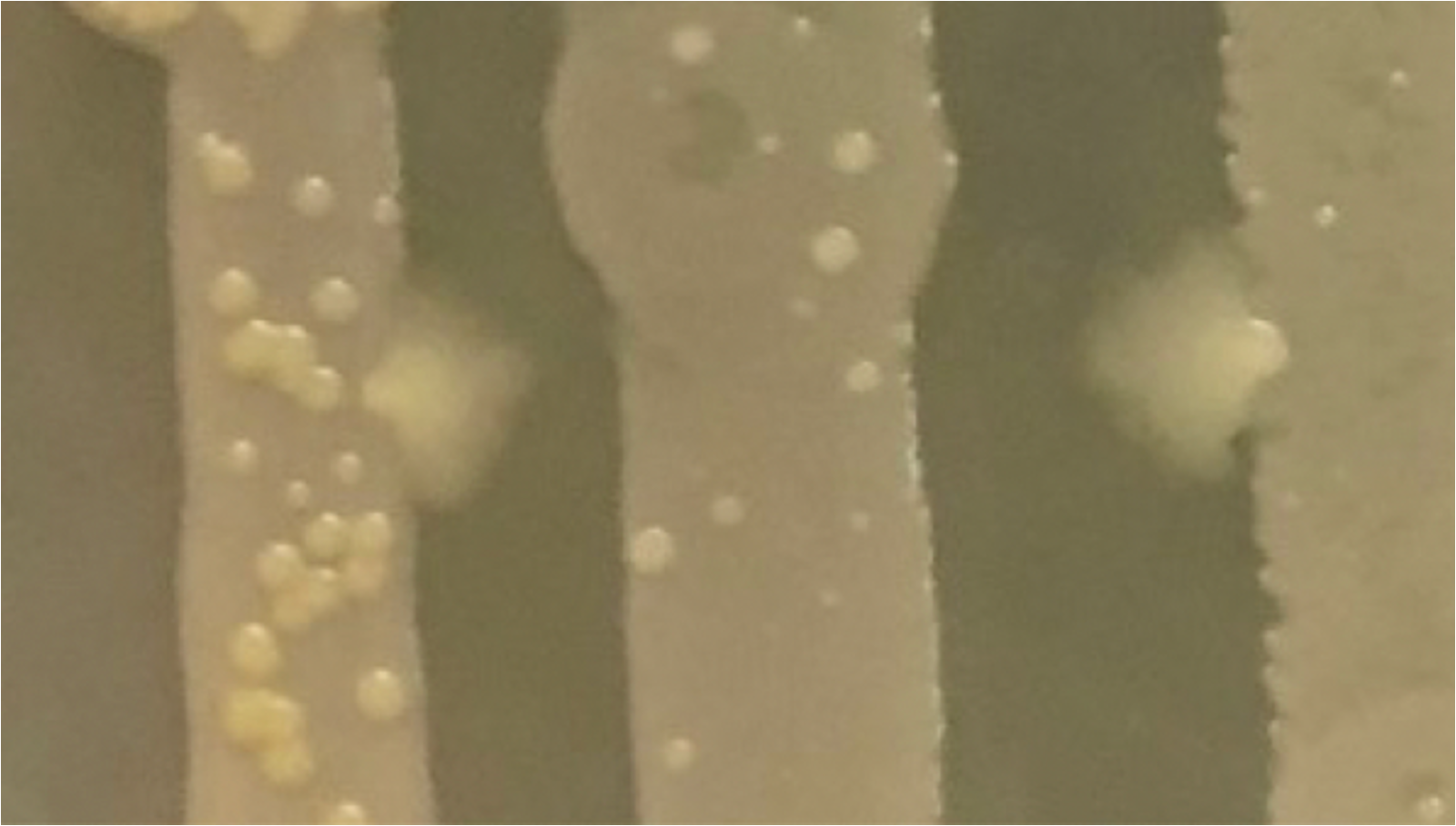

Melanie noticed that in some of her cultures, there would be these much larger colonies that form in and around the more common smaller colonies.  Additionally, we noticed that some of these colonies were showing some signs of increased motility, where they would spread out more than we would typically expect from this mutant strain.

Additionally, we noticed that some of these colonies were showing some signs of increased motility, where they would spread out more than we would typically expect from this mutant strain.

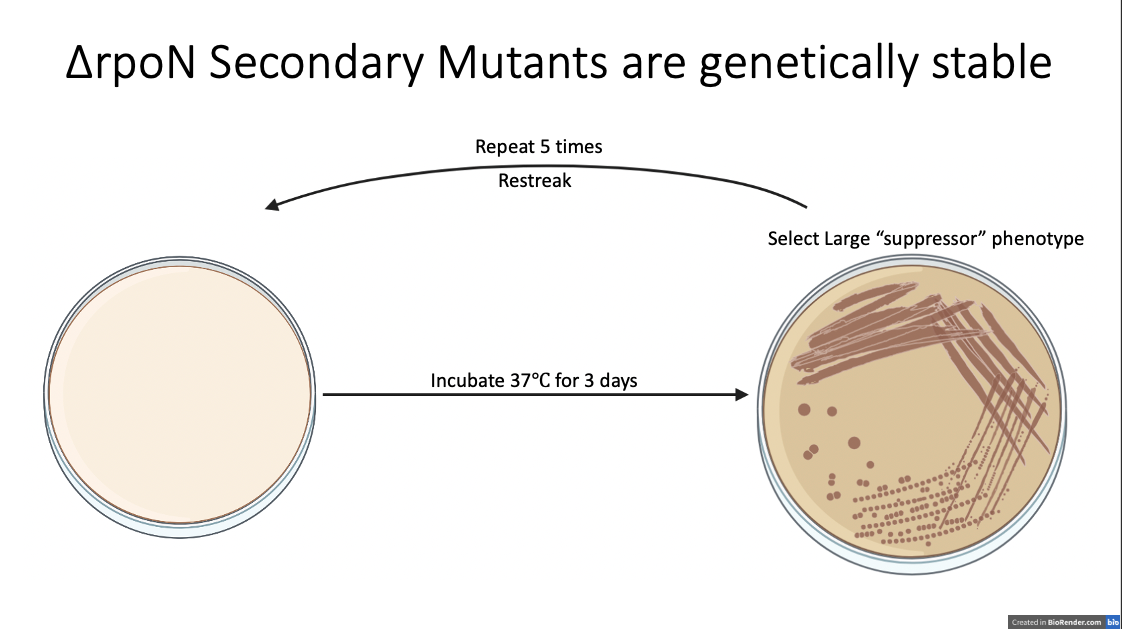

First, I wanted to make sure to isolate these larger colonies so we would have a stable stock to continuously pull from. I started by streaking a large colony onto a plate, incubating for 3 days, then selected another large colony, restreaked again, and continued to do this until I only saw these large colonies forming consistently.

After 5 passages, I isolated six different single colonies. These all showed a consistent large colony phenotype and the large colony size after these continuous passages suggest that whatever is going on is genetically stable and not some impact of the environment that they were growing in. From now on, I’m going to call these isolates secondary mutants since our working hypothesis is that these had some genetic change on top of their rpoN knockout background causing the new phenotype. So, the major question of my rotation was to look at what is responsible for these large colonies? At this point, I hypothesized (and had the time to test) that this phenotype could be the result of increased motility in these new isolates or there could be faster growth occurring.

We suspected that increased motility could be playing a role in the larger colony size because we saw these colonies that seemed to spread out much more than the other smaller colonies on the same plate. Additionally, it is known rpoN is required for the flagellar motility so we would expect to see poor motility in these secondary mutants since they are lacking a functioning rpoN. Since these appeared to have some more motility than the others around them, I first want to determine if these secondary mutants had regained motility despite their rpoN knockout background.

The movement across the top of these plates is known as swarming motility. This movement is driven by the flagella and results in these really pretty growth patterns in P. aeruginosa. Since we know that our rpoN mutants shouldn’t be able to show much motility, this would be a quick and easy way to see if increased flagellar motility is responsible for the growth pattern that we were seeing.

However, when I performed this swarming motility assay, we repeatedly saw that there was no significant difference in the motility ability of our new isolates compared to the parental rpoN knockout strain. I also tested other types of motility, including swimming and twitch motility and these also confirmed these results. And so, we concluded that these secondary mutants don’t show an improvement in their motility over the original parental strain and we can conclude that these secondary mutants have not regained motility

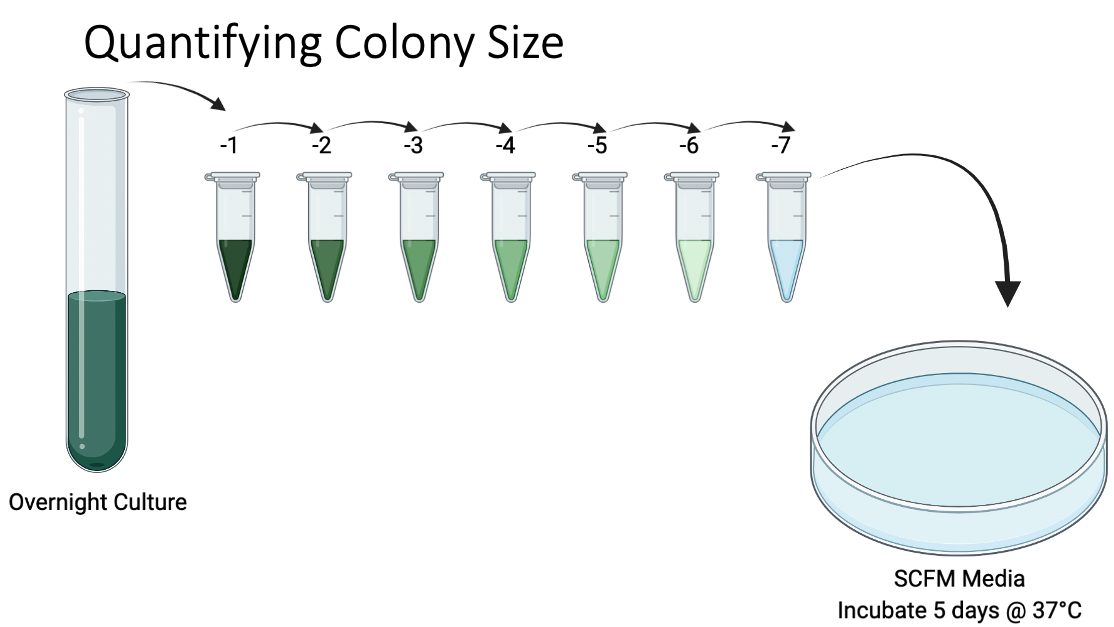

And so at this point, I could rule out increased motility as being responsible for the large colony phenotype that we were observing. This left me suspecting that this increased colony size could be due to faster growth.  To test this, I grew an overnight culture of each of our secondary mutants and the original parental rpoN mutant. I then heavily diluted and plated this overnight culture to obtain single isolated colonies and incubated this on a media mimicking the cystic fibrosis mucus lung environment for five days.

To test this, I grew an overnight culture of each of our secondary mutants and the original parental rpoN mutant. I then heavily diluted and plated this overnight culture to obtain single isolated colonies and incubated this on a media mimicking the cystic fibrosis mucus lung environment for five days.

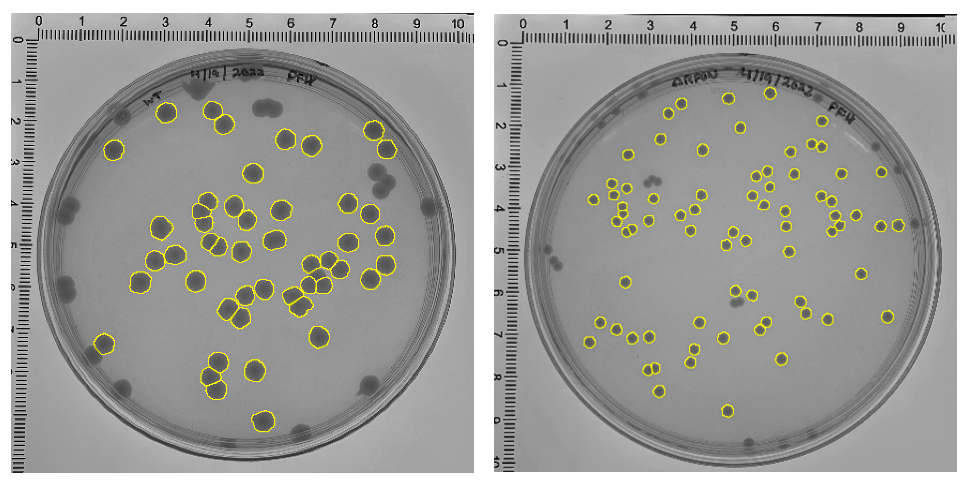

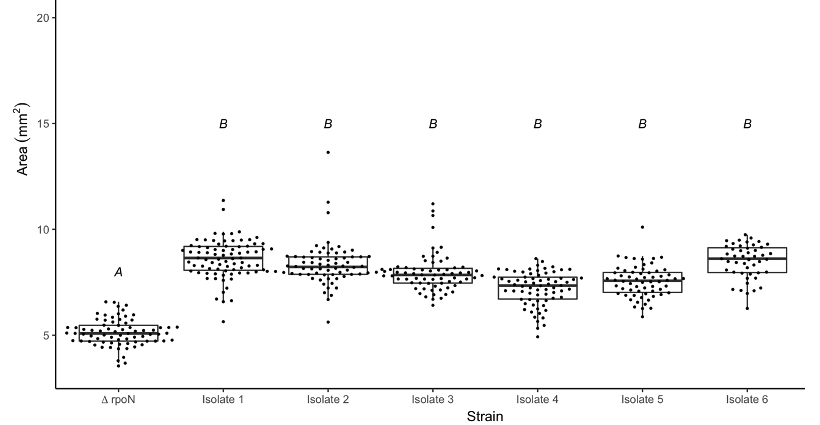

At the end point, I saw that all of the secondary mutants showed a significantly larger colony size compared to the original parental strain. This confirmed that these colonies were in fact larger like I had suspected but this didn’t yet answer the question as to whether these colonies were growing faster.

At the end point, I saw that all of the secondary mutants showed a significantly larger colony size compared to the original parental strain. This confirmed that these colonies were in fact larger like I had suspected but this didn’t yet answer the question as to whether these colonies were growing faster.

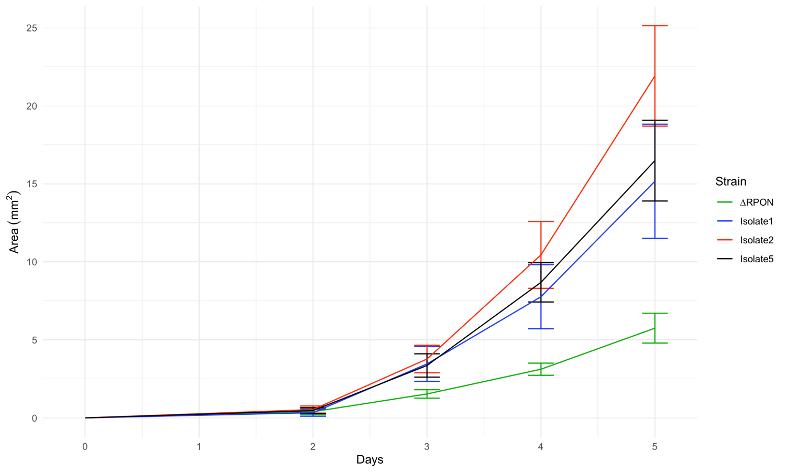

To test this, I quantified the size of the colonies over a 5-day period. This showed that the secondary mutants do in fact show an increased growth rate compared to the original parents rpoN mutant.

|

|

Eventually the secondary mutants do catch up with the WT and begin to have colonies that are about the same size as WT, but this takes a significant amount of time. I never saw the rpoN knockout strain colonies get anywhere close to the size of the WT colonies.

Now that I had confirmed that this colony size difference is due to an increased growth rate, even with the rpoN mutation, we suspected that these isolates must have secondary mutations that are enabling this enhanced growth. And even more, if this rpoN mutant is able to partically rescue its growth back to WT levels, this could be a potential mutation of interest in the chronic wound environment that allows these mutants to compete with other, faster growing strains. So, we wanted to try to determine what genetic changes were underlying the observed phenotype.

To try to figure out if there are secondary mutations responsible for the increased growth I saw, I sent purified genomic DNA to the Microbial Genome Sequencing Center in Pittsburgh. I received back from them raw sequencing reads. I then identified the low-quality reads and removed these from all the future steps in the analysis. Then, using the wild type Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome as a reference, we aligned all our reads and used breseq to identify mutations in our secondary mutants. These steps are visually outlined in the video below!

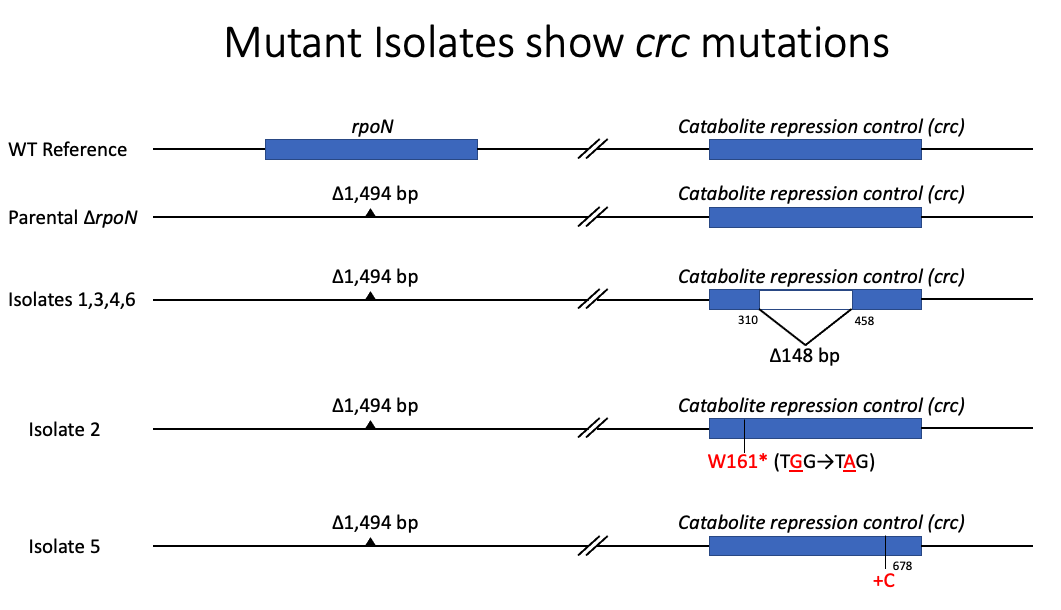

Amazingly, we found that all our mutant isolates had secondary mutations in the same gene. For your reference I’m also showing the wild type reference of the genes we are going to be looking at, rpoN and catabolite repression control (crc).

In the parental rpoN mutant, there is a large deletion that encompasses the entire rpoN coding region and a fully intact crc gene. In 4 of the six isolates that we sent to sequencing, we saw the rpoN deletion like we were expecting. But on top of the rpoN deletion, we also saw a large out of frame deletion in the crc gene. In another isolate, we saw a very early premature stop codon caused by a single basepair change. Lastly, one of our isolates had an insertion that caused a frameshift. Even though this is later in the crc gene, we believe that this is still a detrimental mutation since we observed the same phenotype in this strain as in all the other strains that had more severe mutations.

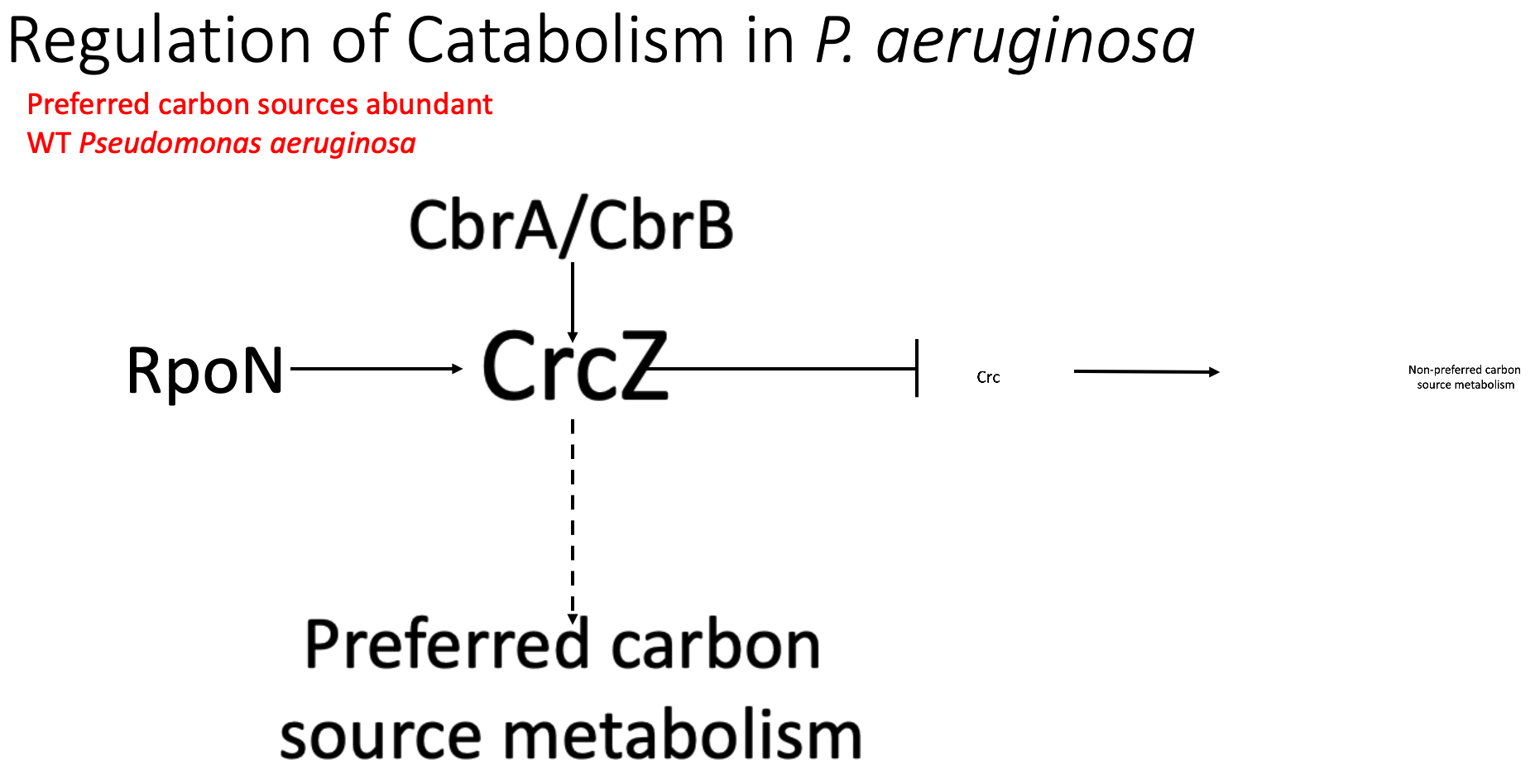

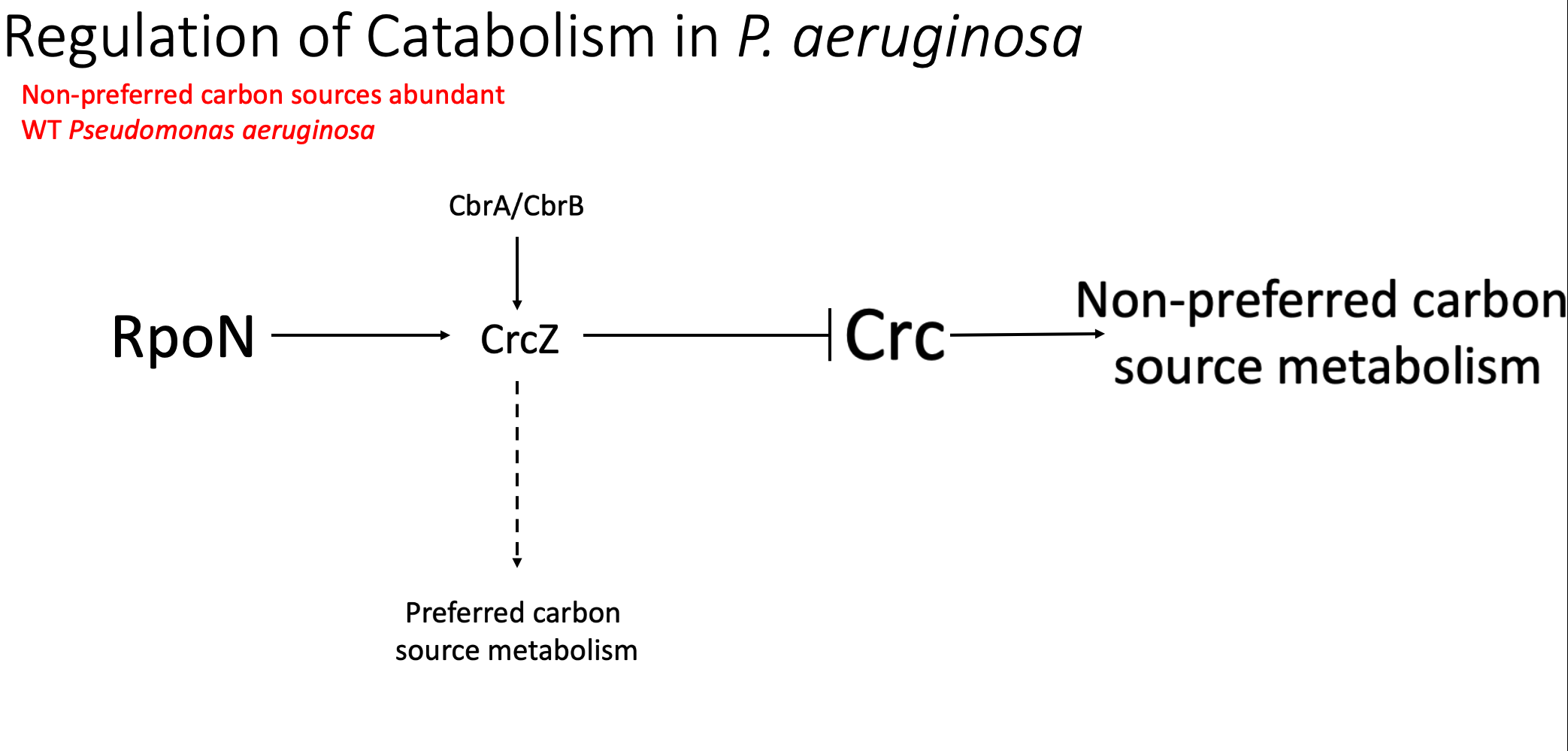

So, what is this crc gene and what does it do in Pseudomonas? Pseudomonas can preferentially use different carbon sources, including either preferred carbon sources such as succinate or non-preferred carbon sources like glucose. This is important for pseudomonas because it does not make sense to create gene products for a metabolism pathway that you may not be using at the time based on the nutritional environment that you are in. CRC acts as a major regulator in deciding which carbon source will be used. crc promotes carbohydrate metabolism, or the use of non-preferred carbon sources. CRCz, a small regulatory RNA inhibits CRC activity, thus indirectly promoting the use of preferred carbon sources. In wild type P aeruginosa, rpoN is required for the expression of crcZ. And the regulation of this entire system is thought to come from CbrA and CbrB. When a preferred carbon source is abundant, the amount of crcZ increases, significantly decreasing the amount of active CRC and decreasing the expression of carbohydrate metabolism genes. This leads to utilization of these preferred carbon sources.

|

|

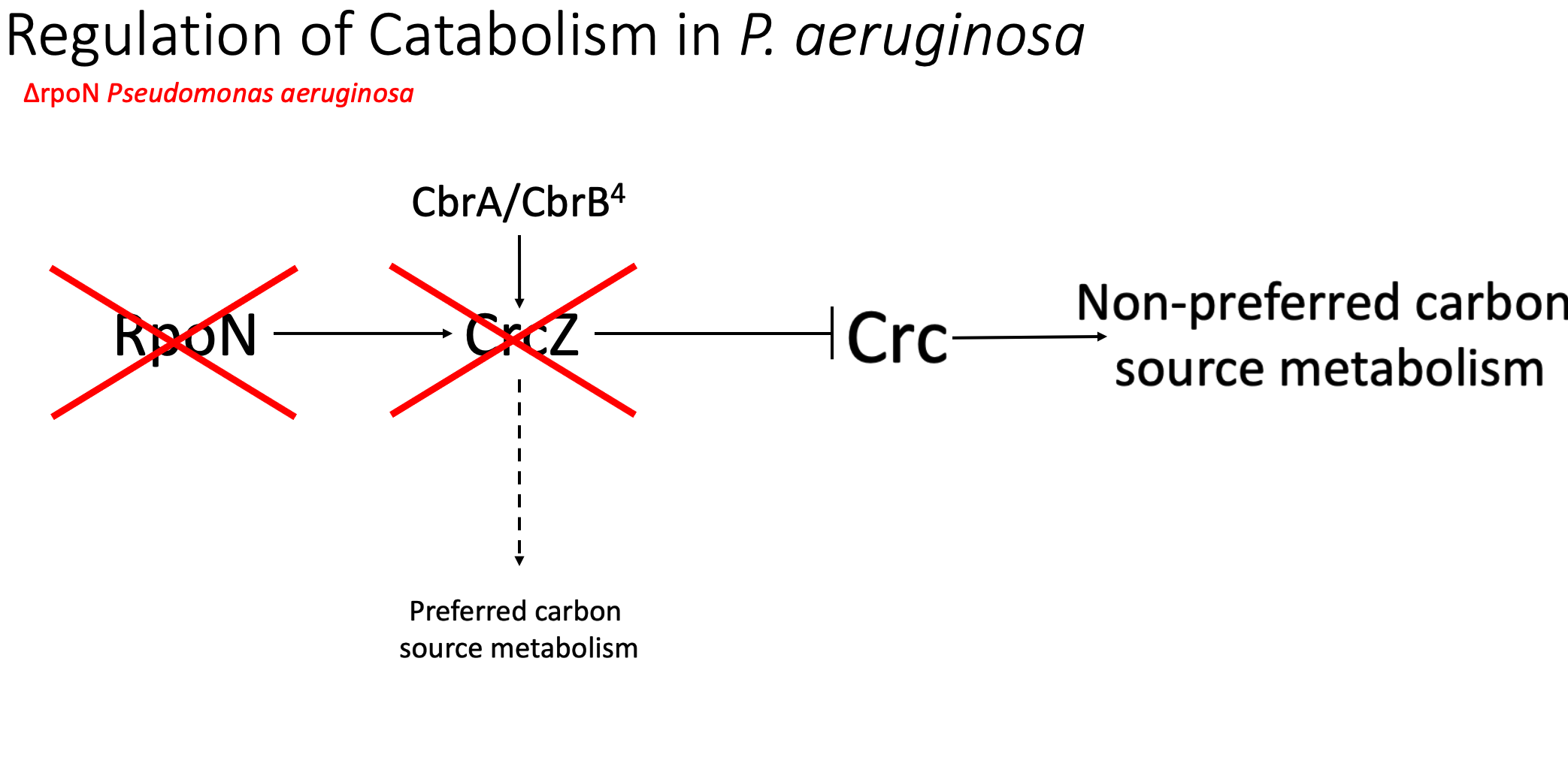

In the parental rpoN strain, there is no functional RPON and because rpoN is required for the transcription of crcZ, there can be no crcZ expression. And so there will be no controlled expression of preferential catabolism genes or the downregulation of non-preferred catabolism genes. Without this regulation, there is likely a significant overexpression of CRC and carbohydrate metabolism genes, meaning that more inefficient catabolism is always being performed, likely explaining the significantly decreased growth in the parental rpoN mutants.

So, I hypothesized that our rpoN mutants are essentially stuck performing this non-preferred carbon source metabolism, no matter the environment that the nutritional environment that they are in. And building on this, we believe that one way that these rpoN mutants can try to alleviate this metabolic stress and regain some balance metabolically is to mutate and break the function of crc. In the new crc mutants, I believe that there is no functional or significantly less functioning CRC protein. This means that there is likely no induced expression of carbohydrate metabolism genes and no controlled breakdown of non-preferred carbon sources, potentially rebalancing the metabolic state in Pseudomonas and allowing for more efficient growth.

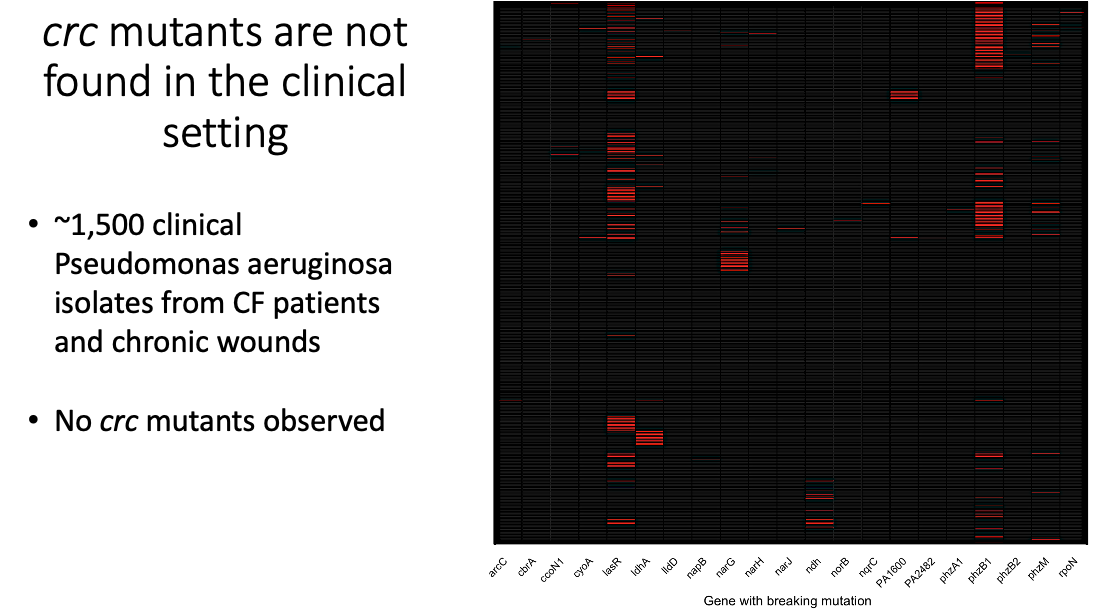

Lastly, I wanted to know if crc mutations show up in clinical cases of P aeruginosa in people with cystic fibrosis and chronic wounds. This analysis revealed that many of the same genes, like lasR, the Nap, and the Nar family of genes that routinely are found in P. aeruginosa infectious strains, showed up again and again. We did also see some rpoN mutants, but there were zero isolates with mutants in the crc gene, suggesting that this is not a clinically relevant mutation and is likely an artifact of the lab environment.

This is an important takeaway because most of our work is in the lab and this is a strong reminder that we, either intentionally or unintentionally, are providing a selective pressure for the microbes that we work with in the lab. And this lab selective pressure can lead to secondary mutants, so we should be cognoscente of these in our research.

Overall, I found that the increased colony size that we observed was a genetically stable phenotype and was due to an increased growth rate over time. Because this was a genetically stable phenotype, I suspected that there could be a secondary mutation responsible for the larger colony size. After performing whole genome sequencing and comparing the assembled genome to the reference parent strain, I found that all strains shared a mutation in the crc gene, a catabolite regulatory gene. Lastly, the analysis of clinical isolates showed that RPON mutants are found in chronic infections contexts but that crc mutants are not.

Previously, there has been transcriptional and metabolic profiling of rpoN, crcZ, and crc mutants but I couldn’t find any profiling of mutants with multiple mutations. In the future, Studies utilizing mutants with multiple knockouts could begin to determine how Pseudomonas is still maintaining metabolic control and potentially increasing its growth even with the absence of these key regulatory genes. At this time, we have no understanding of what substrates these rpoN- / crc-null strains are using, and we don’t know how regulation has been altered in these strains.

I can’t say enough good things about all of the support and knowledge that I gained throughout this rotation from everyone in the Spero lab. Melanie and Alison were both amazing, and I had the best rotation mates in Sophia and Rob!